Book Of Judith on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Book of Judith is a

The Book of Judith is a

/ref> Reasons for its exclusion include the lateness of its composition, possible Greek origin, open support of the

::C'. Judith and her maid return to Bethulia (13.10b–11)

:B'. Judith plans the destruction of Israel's enemy (13:12–16:20)

A'. Conclusion about Judith (16.1–25)

Similarly, parallels within Part II are noted in comments within the

::C'. Judith and her maid return to Bethulia (13.10b–11)

:B'. Judith plans the destruction of Israel's enemy (13:12–16:20)

A'. Conclusion about Judith (16.1–25)

Similarly, parallels within Part II are noted in comments within the

Holofernes, the

Holofernes, the

Judith 12: Notes & Commentary

accessed 31 October 2022 He brought in Judith to recline with Holofernes and was the first one who discovered his beheading. Uzziah or Oziah, governor of Bethulia; together with Cabri and Carmi, he rules over Judith's city. When the city is besieged by the Assyrians and the water supply dries up, he agrees to the people's call to surrender if God has not rescued them within five days, a decision challenged as "rash" by Judith.

The Oxford Bible Commentary

p. 638 "loudly proclaimed" in advance of her actions in the following chapters. This runs to 14 verses in English versions, 19 verses in the Vulgate.

It is generally accepted that the Book of Judith is ahistorical. The fictional nature "is evident from its blending of history and fiction, beginning in the very first verse, and is too prevalent thereafter to be considered as the result of mere historical mistakes."

Thus, the great villain is "Nebuchadnezzar, who ruled over the ''

It is generally accepted that the Book of Judith is ahistorical. The fictional nature "is evident from its blending of history and fiction, beginning in the very first verse, and is too prevalent thereafter to be considered as the result of mere historical mistakes."

Thus, the great villain is "Nebuchadnezzar, who ruled over the ''

The first extant commentary on The Book of Judith is by

The first extant commentary on The Book of Judith is by

The subject is one of the most commonly shown in the

The subject is one of the most commonly shown in the

Arnold Bennett: "Judith"

Gutenberg Ed. In 1981, the play "Judith among the Lepers" by the Israeli (Hebrew) playwright

The Book of Judith

Full text (also available i

* Craven, Ton

Judith: Apocrypha

''The Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women'' 31 December 1999 at Jewish Women's Archive * Toy, Crawford Howell; Charles Cutler Torrey, Torrey, Charles C.

JUDITH, BOOK OF

at ''The Jewish Encyclopedia'', 1906 * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Judith, Book of Book of Judith Deuterocanonical books Ancient Hebrew texts Historical novels Jewish apocrypha Biblical women in ancient warfare Historical books

The Book of Judith is a

The Book of Judith is a deuterocanonical

The deuterocanonical books (from the Greek meaning "belonging to the second canon") are books and passages considered by the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, and the Assyrian Church of the East to be ...

book, included in the Septuagint

The Greek Old Testament, or Septuagint (, ; from the la, septuaginta, lit=seventy; often abbreviated ''70''; in Roman numerals, LXX), is the earliest extant Greek translation of books from the Hebrew Bible. It includes several books beyond th ...

and the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or "canonical") ...

Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

of the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

, but excluded from the Hebrew canon and assigned by Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

s to the apocrypha

Apocrypha are works, usually written, of unknown authorship or of doubtful origin. The word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to writings which were kept secret because they were the vehicles of esoteric knowledge considered ...

. It tells of a Jewish widow, Judith, who uses her beauty and charm to destroy an Assyrian general and save Israel from oppression. The surviving Greek manuscripts contain several historical anachronism

An anachronism (from the Ancient Greek, Greek , 'against' and , 'time') is a chronology, chronological inconsistency in some arrangement, especially a juxtaposition of people, events, objects, language terms and customs from different time per ...

s, which is why some Protestant scholars now consider the book non-historical: a parable

A parable is a succinct, didactic story, in prose or verse, that illustrates one or more instructive lessons or principles. It differs from a fable in that fables employ animals, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature as characters, w ...

, a theological novel, or perhaps the first historical novel

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

.

The name Judith (), meaning "Praised" or "Jewess", is the feminine form of Judah.

Historical context

Original language

It is not clear whether the Book of Judith was originally written in Hebrew or in Greek. The oldest existing version is in theSeptuagint

The Greek Old Testament, or Septuagint (, ; from the la, septuaginta, lit=seventy; often abbreviated ''70''; in Roman numerals, LXX), is the earliest extant Greek translation of books from the Hebrew Bible. It includes several books beyond th ...

, and might either be a translation from Hebrew or composed in Greek. Details of vocabulary and phrasing point to a Greek text written in a language modeled on the Greek developed through translating the other books in the Septuagint.

The extant Hebrew language

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

versions, whether identical to the Greek, or in the shorter Hebrew version, date to the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

. The Hebrew versions name important figures directly such as the Seleucid

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

king Antiochus IV Epiphanes

Antiochus IV Epiphanes (; grc, Ἀντίοχος ὁ Ἐπιφανής, ''Antíochos ho Epiphanḗs'', "God Manifest"; c. 215 BC – November/December 164 BC) was a Greek Hellenistic king who ruled the Seleucid Empire from 175 BC until his deat ...

, thus placing the events in the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 3 ...

when the Maccabees

The Maccabees (), also spelled Machabees ( he, מַכַּבִּים, or , ; la, Machabaei or ; grc, Μακκαβαῖοι, ), were a group of Jewish rebel warriors who took control of Judea, which at the time was part of the Seleucid Empire. ...

battled the Seleucid monarchs. The Greek version uses deliberately cryptic and anachronistic

An anachronism (from the Greek , 'against' and , 'time') is a chronological inconsistency in some arrangement, especially a juxtaposition of people, events, objects, language terms and customs from different time periods. The most common type ...

references such as " Nebuchadnezzar", a " King of Assyria", who "reigns in Nineveh", for the same king. The adoption of that name, though unhistorical, has been sometimes explained either as a copyist's addition, or an arbitrary name assigned to the ruler of Babylon.

Canonicity

In Judaism

Although the author was likely Jewish, there is no evidence that the Book of Judith was ever considered authoritative or a candidate for canonicity by any Jewish group. TheMasoretic Text

The Masoretic Text (MT or 𝕸; he, נֻסָּח הַמָּסוֹרָה, Nūssāḥ Hammāsōrā, lit. 'Text of the Tradition') is the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) in Rabbinic Judaism. ...

of the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

does not contain it, nor was it found among the ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls (also the Qumran Caves Scrolls) are ancient Jewish and Hebrew religious manuscripts discovered between 1946 and 1956 at the Qumran Caves in what was then Mandatory Palestine, near Ein Feshkha in the West Bank, on the nor ...

or referred to in any early Rabbinic literature.Flint, Peter & VanderKam, James, ''The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Their Significance For Understanding the Bible, Judaism, Jesus, and Christianity'', Continuum International, 2010, p. 160 (Protestant Canon) and p. 209 (Judith not among Dead Sea Scrolls)/ref> Reasons for its exclusion include the lateness of its composition, possible Greek origin, open support of the

Hasmonean dynasty

The Hasmonean dynasty (; he, ''Ḥašmōnaʾīm'') was a ruling dynasty of Judea and surrounding regions during classical antiquity, from BCE to 37 BCE. Between and BCE the dynasty ruled Judea semi-autonomously in the Seleucid Empire, and ...

(to which the early rabbinate was opposed), and perhaps the brash and seductive character of Judith herself.

However, after disappearing from circulation among Jews for over a millennium, references to the Book of Judith, and the figure of Judith herself, resurfaced in the religious literature of crypto-Jews

Crypto-Judaism is the secret adherence to Judaism while publicly professing to be of another faith; practitioners are referred to as "crypto-Jews" (origin from Greek ''kryptos'' – , 'hidden').

The term is especially applied historically to Sp ...

who escaped Christian persecution after the capitulation of the Caliphate of Córdoba

The Caliphate of Córdoba ( ar, خلافة قرطبة; transliterated ''Khilāfat Qurṭuba''), also known as the Cordoban Caliphate was an Islamic state ruled by the Umayyad dynasty from 929 to 1031. Its territory comprised Iberia and parts o ...

. The renewed interest took the form of "tales of the heroine, liturgical poems, commentaries on the Talmud, and passages in Jewish legal codes."

Although the text itself does not mention Hanukkah, it became customary for a Hebrew midrash

''Midrash'' (;"midrash"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

ic variant of the Judith story to be read on the ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; he, שַׁבָּת, Šabbāṯ, , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the week—i.e., Saturday. On this day, religious Jews remember the biblical storie ...

of Hanukkah

or English translation: 'Establishing' or 'Dedication' (of the Temple in Jerusalem)

, nickname =

, observedby = Jews

, begins = 25 Kislev

, ends = 2 Tevet or 3 Tevet

, celebrations = Lighting candles each night. ...

as the story of Hanukkah takes place during the time of the Hasmonean dynasty.

That midrash, whose heroine is portrayed as gorging the enemy on cheese and wine before cutting off his head, may have formed the basis of the minor Jewish tradition to eat dairy products during Hanukkah.

In that respect, Medieval Jewry appears to have viewed Judith as the Hasmonean counterpart to Queen Esther, the heroine of the holiday of Purim

Purim (; , ; see Name below) is a Jewish holiday which commemorates the saving of the Jewish people from Haman, an official of the Achaemenid Empire who was planning to have all of Persia's Jewish subjects killed, as recounted in the Book ...

. The textual reliability of the Book of Judith was also taken for granted, to the extent that Biblical commentator Nachmanides (Ramban) quoted several passages from a Peshitta

The Peshitta ( syc, ܦܫܺܝܛܬܳܐ ''or'' ') is the standard version of the Bible for churches in the Syriac tradition, including the Maronite Church, the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Syriac Catholic Church, the Syriac Orthodox Church, ...

(Syriac version) of Judith in support of his rendering of Deuteronomy 21:14.

In Christianity

Although early Christians, such asClement of Rome

Pope Clement I ( la, Clemens Romanus; Greek: grc, Κλήμης Ῥώμης, Klēmēs Rōmēs) ( – 99 AD) was bishop of Rome in the late first century AD. He is listed by Irenaeus and Tertullian as the bishop of Rome, holding office from 88 AD ...

, Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

, and Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria ( grc , Κλήμης ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; – ), was a Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen and ...

, read and used the Book of Judith, some of the oldest Christian canons, including the Bryennios List (1st/2nd century), that of Melito of Sardis

Melito of Sardis ( el, Μελίτων Σάρδεων ''Melítōn Sárdeōn''; died ) was the bishop of Sardis near Smyrna in western Anatolia, and a great authority in early Christianity. Melito held a foremost place in terms of bishops in Asia ...

(2nd century) and Origen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an Early Christianity, early Christian scholar, ...

(3rd century), do not include it. Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, th ...

, when he produced his Latin translation, the Vulgate

The Vulgate (; also called (Bible in common tongue), ) is a late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bible.

The Vulgate is largely the work of Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Gospels u ...

, counted it among the apocrypha, (although he changed his mind and later quoted it as scripture, and said he merely expressed the views of the Jews), as did Athanasius

Athanasius I of Alexandria, ; cop, ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲡⲓⲁⲡⲟⲥⲧⲟⲗⲓⲕⲟⲥ or Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲁ̅; (c. 296–298 – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, ...

, Cyril of Jerusalem and Epiphanius of Salamis

Epiphanius of Salamis ( grc-gre, Ἐπιφάνιος; c. 310–320 – 403) was the bishop of Salamis, Cyprus, at the end of the 4th century. He is considered a saint and a Church Father by both the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Churches. He g ...

.

However, some influential fathers of the Church, including Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berbers, Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia (Roman pr ...

, Ambrose

Ambrose of Milan ( la, Aurelius Ambrosius; ), venerated as Saint Ambrose, ; lmo, Sant Ambroeus . was a theologian and statesman who served as Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He expressed himself prominently as a public figure, fiercely promo ...

, and Hilary of Poitiers

Hilary of Poitiers ( la, Hilarius Pictaviensis; ) was Bishop of Poitiers and a Doctor of the Church. He was sometimes referred to as the "Hammer of the Arians" () and the "Athanasius of the West". His name comes from the Latin word for happy or ...

, considered Judith sacred scripture, and Pope Innocent I

Pope Innocent I ( la, Innocentius I) was the bishop of Rome from 401 to his death on 12 March 417. From the beginning of his papacy, he was seen as the general arbitrator of ecclesiastical disputes in both the East and the West. He confirmed the ...

declared it part of the canon. In Jerome's ''Prologue to Judith'' he claims that the Book of Judith was "found by the Nicene Council to have been counted among the number of the Sacred Scriptures". However, no such declaration has been found in the Canons of Nicaea, and it is uncertain whether Jerome is referring to the use made of the book in the discussions of the council, or whether he was misled by some spurious canons attributed to that council.

It was also accepted by the councils of Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

(382), Hippo

The hippopotamus ( ; : hippopotamuses or hippopotami; ''Hippopotamus amphibius''), also called the hippo, common hippopotamus, or river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic mammal native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is one of only two extant ...

(393), Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

(397), Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

(1442) and eventually dogmatically defined as canonical by the Roman Catholic Church in 1546 in the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trento, Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italian Peninsula, Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation ...

. The Eastern Orthodox Church also accepts Judith as inspired scripture, as was confirmed in the Synod of Jerusalem in 1672.

The canonicity of Judith is typically rejected by Protestants, who accept as the Old Testament only those books that are found in the Jewish canon. Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

viewed the book as an allegory, but listed it as the first of the eight writings in his Apocrypha. In Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

, it has the intermediate authority of the Apocrypha of the OT, regarded as useful or edifying but not to be taken as a basis for establishing doctrine.

Judith is also referred to in chapter 28 of 1 Meqabyan, a book considered canonical in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church ( am, የኢትዮጵያ ኦርቶዶክስ ተዋሕዶ ቤተ ክርስቲያን, ''Yäityop'ya ortodoks täwahedo bétäkrestyan'') is the largest of the Oriental Orthodox Churches. One of the few Chris ...

.

Contents

Plot summary

The story revolves around Judith, a daring and beautiful widow, who is upset with her Jewish countrymen for not trusting God to deliver them from their foreign conquerors. She goes with her loyal maid to the camp of the enemy general,Holofernes

In the deuterocanonical Book of Judith, Holofernes ( grc, Ὀλοφέρνης; he, הולופרנס) was an invading Assyrian general known for having been beheaded by Judith, a Hebrew widow who entered his camp and beheaded him while he was ...

, with whom she slowly ingratiates herself, promising him information on the Israelites. Gaining his trust, she is allowed access to his tent one night as he lies in a drunken stupor. She decapitates him, then takes his head back to her fearful countrymen. The Assyrians, having lost their leader, disperse, and Israel is saved. Though she is courted by many, Judith remains unmarried for the rest of her life.

Literary structure

The Book of Judith can be split into two parts or "acts" of approximately equal length. Chapters 1–7 describe the rise of the threat to Israel, led by the evil king Nebuchadnezzar and his sycophantic general Holofernes, and is concluded as Holofernes' worldwide campaign has converged at the mountain pass where Judith's village, Bethulia, is located. Chapters 8–16 then introduce Judith and depict her heroic actions to save her people. The first part, although at times tedious in its description of the military developments, develops important themes by alternating battles with reflections and rousing action with rest. In contrast, the second half is devoted mainly to Judith's strength of character and the beheading scene. The New Oxford Annotated Apocrypha identifies a clearchiastic

In rhetoric, chiasmus ( ) or, less commonly, chiasm (Latin term from Greek , "crossing", from the Greek , , "to shape like the letter Χ"), is a "reversal of grammatical structures in successive phrases or clauses – but no repetition of wo ...

pattern in both "acts", in which the order of events is reversed at a central moment in the narrative (i.e., abcc'b'a').

Part I (1:1–7:23)

A. Campaign against disobedient nations; the people surrender (1:1–2:13)

:B. Israel is "greatly terrified" (2:14–3:10)

::C. Joakim

Joakim or Joacim is a male given name primarily used in Scandinavian languages and Finnish. It is derived from a transliteration of the Hebrew יהוֹיָקִים, and literally means "lifted by Jehovah".

In the Old Testament, Jehoiakim was a ...

prepares for war (4:1–15)

:::D. Holofernes talks with Achior (5:1–6.9)

::::E. Achior is expelled by Assyrians (6:10–13)

::::E'. Achior is received in the village of Bethulia (6:14–15)

:::D'. Achior talks with the people (6:16–21)

::C'. Holofernes prepares for war (7:1–3)

:B'. Israel is "greatly terrified" (7:4–5)

A'. Campaign against Bethulia; the people want to surrender (7:6–32)

Part II (8:1–16:25)

A. Introduction of Judith (8:1–8)

:B. Judith plans to save Israel (8:9–10:8), including her extended prayer

Prayer is an invocation or act that seeks to activate a rapport with an object of worship through deliberate communication. In the narrow sense, the term refers to an act of supplication or intercession directed towards a deity or a deified a ...

(9:1-14)

::C. Judith and her maid leave Bethulia (10:9–10)

:::D. Judith beheads Holofernes (10:11–13:10a)

::C'. Judith and her maid return to Bethulia (13.10b–11)

:B'. Judith plans the destruction of Israel's enemy (13:12–16:20)

A'. Conclusion about Judith (16.1–25)

Similarly, parallels within Part II are noted in comments within the

::C'. Judith and her maid return to Bethulia (13.10b–11)

:B'. Judith plans the destruction of Israel's enemy (13:12–16:20)

A'. Conclusion about Judith (16.1–25)

Similarly, parallels within Part II are noted in comments within the New American Bible Revised Edition

The New American Bible Revised Edition (NABRE) is an English-language Catholic translation of the Bible, the first major update in 20 years to the New American Bible (NAB), which was translated by members of the Catholic Biblical Association an ...

: Judith summons a town meeting in Judith 8:10 in advance of her expedition and is acclaimed by such a meeting in Judith 13:12-13; Uzziah blesses Judith in advance in Judith 8:5 and afterwards in Judith 13:18-20.

Literary genre

Most contemporaryexegetes

Exegesis ( ; from the Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Biblical works. In modern usage, exegesis can involve critical interpretation ...

, such as Biblical scholar Gianfranco Ravasi

Gianfranco Ravasi (born 18 October 1942) is an Italian prelate of the Catholic Church and a biblical scholar. A cardinal since 2010, he was President of the Pontifical Council for Culture from 2007 to 2022. He headed Milan's Ambrosian Librar ...

, generally tend to ascribe Judith to one of several contemporaneous literary genres, reading it as an extended parable in the form of a historical fiction

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

, or a propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

literary work from the days of the Seleucid oppression.

It has also been called "an example of the ancient Jewish novel in the Greco-Roman period". Other scholars note that Judith fits within and even incorporates the genre of "salvation traditions" from the Old Testament, particularly the story of Deborah

According to the Book of Judges, Deborah ( he, דְּבוֹרָה, ''Dəḇōrā'', "bee") was a prophetess of the God of the Israelites, the fourth Judge of pre-monarchic Israel and the only female judge mentioned in the Bible. Many scholars ...

and Jael

Jael or Yael ( he, יָעֵל ''Yāʿēl'') is the name of the heroine who delivered Israel from the army of King Jabin of Canaan in the Book of Judges of the Hebrew Bible. After Barak demurred at the behest of the prophetess Deborah, God turned ...

(Judges

A judge is an official who presides over a court.

Judge or Judges may also refer to:

Roles

*Judge, an alternative name for an adjudicator in a competition in theatre, music, sport, etc.

*Judge, an alternative name/aviator call sign for a membe ...

4–5), who seduced and inebriated the Canaanite commander Sisera

Sisera ( he, סִיסְרָא ''Sîsərā'') was commander of the Canaanite army of King Jabin of Hazor, who is mentioned in of the Hebrew Bible. After being defeated by the forces of the Israelite tribes of Zebulun and Naphtali under the com ...

before hammering a tent-peg into his forehead.

There are also thematic connections to the revenge of Simeon

Simeon () is a given name, from the Hebrew (Biblical ''Šimʿon'', Tiberian ''Šimʿôn''), usually transliterated as Shimon. In Greek it is written Συμεών, hence the Latinized spelling Symeon.

Meaning

The name is derived from Simeon, so ...

and Levi

Levi (; ) was, according to the Book of Genesis, the third of the six sons of Jacob and Leah (Jacob's third son), and the founder of the Israelite Tribe of Levi (the Levites, including the Kohanim) and the great-grandfather of Aaron, Moses and ...

on Shechem after the rape of Dinah in Genesis 34.

In the Christian West from the patristic period on, Judith was invoked in a wide variety of texts as a multi-faceted allegorical figure. As a "''Mulier sancta''", she personified the Church and many virtues

Virtue ( la, virtus) is moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. In other words, it is a behavior that shows high moral standard ...

– Humility

Humility is the quality of being humble. Dictionary definitions accentuate humility as a low self-regard and sense of unworthiness. In a religious context humility can mean a recognition of self in relation to a deity (i.e. God), and subsequent ...

, Justice

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

, Fortitude, Chastity

Chastity, also known as purity, is a virtue related to temperance. Someone who is ''chaste'' refrains either from sexual activity considered immoral or any sexual activity, according to their state of life. In some contexts, for example when mak ...

(the opposite of Holofernes' vices

A vice is a practice, behaviour, or Habit (psychology), habit generally considered immorality, immoral, sinful, crime, criminal, rude, taboo, depraved, degrading, deviant or perverted in the associated society. In more minor usage, vice can refe ...

Pride

Pride is defined by Merriam-Webster as "reasonable self-esteem" or "confidence and satisfaction in oneself". A healthy amount of pride is good, however, pride sometimes is used interchangeably with "conceit" or "arrogance" (among other words) wh ...

, Tyranny

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to ...

, Decadence

The word decadence, which at first meant simply "decline" in an abstract sense, is now most often used to refer to a perceived decay in standards, morals, dignity, religious faith, honor, discipline, or skill at governing among the members of ...

, Lust

Lust is a psychological force producing intense desire for something, or circumstance while already having a significant amount of the desired object. Lust can take any form such as the lust for sexuality (see libido), money, or power. It c ...

) – and she was, like the other heroic women of the Hebrew scriptural tradition, made into a typological prefiguration of the Virgin Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

. Her gender made her a natural example of the biblical paradox of "strength in weakness"; she is thus paired with David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

and her beheading of Holofernes paralleled with that of Goliath – both deeds saved the Covenant People from a militarily superior enemy.

Main characters

Judith, the heroine of the book, introduced in chapter 8. A God-fearing woman, she is the daughter of Merari, a Simeonite, and widow of a certainManasseh

Manasseh () is both a given name and a surname. Its variants include Manasses and Manasse.

Notable people with the name include:

Surname

* Ezekiel Saleh Manasseh (died 1944), Singaporean rice and opium merchant and hotelier

* Jacob Manasseh (die ...

or Manasses, a wealthy farmer. She sends her maid or "waitingwoman" to Uzziah to challenge his decision to capitulate to the Assyrians if God has not rescued the people of Bethulia within five days, and she uses her charm to become an intimate friend of Holofernes, but beheads him allowing Israel to counter-attack the Assyrians. Judith's maid, not named in the story, remains with her throughout the narrative and is given her freedom as the story ends.

Holofernes, the

Holofernes, the villain

A villain (also known as a "black hat" or "bad guy"; the feminine form is villainess) is a stock character, whether based on a historical narrative or one of literary fiction. ''Random House Unabridged Dictionary'' defines such a character a ...

of the book. He is a dedicated soldier of his king, general-in-chief of his army, whom he wants to see exalted in all lands. He is given the task of destroying the rebels who did not support the king of Nineveh in his resistance against Cheleud and the king of Media, until Israel also becomes a target of his military campaign. Judith's courage and charm occasion his death.

Nebuchadnezzar, claimed here to be the king of Nineveh and Assyria. He is so proud that he wants to affirm his strength as a sort of divine power, although Holofernes, his Turtan (commanding general), goes beyond the king's orders when he calls on the western nations to "worship only Nebuchadnezzar, and ... invoke him as a god". Holofernes is ordered to take revenge on those who refused to ally themselves with Nebuchadnezzar.

Achior, an Ammon

Ammon (Ammonite: 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''ʻAmān''; he, עַמּוֹן ''ʻAmmōn''; ar, عمّون, ʻAmmūn) was an ancient Semitic-speaking nation occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Arnon and Jabbok, in p ...

ite leader at Nebuchadnezzar's court; in chapter 5 he summarises the history of Israel

Israel, also known as the Holy Land or Palestine, is the birthplace of the Jewish people, the place where the final form of the Hebrew Bible is thought to have been compiled, and the birthplace of Judaism and Christianity. In the course of ...

and warns the king of Assyria of the power of their God, the "God of heaven", but is mocked. He is protected by the people of Bethulia and becomes a Jew and is circumcised

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. Topic ...

on hearing what Judith has accomplished.

Bagoas, or Vagao (Vulgate), the eunuch

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2nd millennium ...

who had charge over Holofernes' personal affairs. His name is Persian for a eunuch. Haydock, G. L.Judith 12: Notes & Commentary

accessed 31 October 2022 He brought in Judith to recline with Holofernes and was the first one who discovered his beheading. Uzziah or Oziah, governor of Bethulia; together with Cabri and Carmi, he rules over Judith's city. When the city is besieged by the Assyrians and the water supply dries up, he agrees to the people's call to surrender if God has not rescued them within five days, a decision challenged as "rash" by Judith.

Judith's prayer

Chapter 9 constitutes Judith's "extended prayer", Levine, A., ''41. Judith'', in Barton, J. and Muddiman, J. (2001)The Oxford Bible Commentary

p. 638 "loudly proclaimed" in advance of her actions in the following chapters. This runs to 14 verses in English versions, 19 verses in the Vulgate.

Historicity of Judith

It is generally accepted that the Book of Judith is ahistorical. The fictional nature "is evident from its blending of history and fiction, beginning in the very first verse, and is too prevalent thereafter to be considered as the result of mere historical mistakes."

Thus, the great villain is "Nebuchadnezzar, who ruled over the ''

It is generally accepted that the Book of Judith is ahistorical. The fictional nature "is evident from its blending of history and fiction, beginning in the very first verse, and is too prevalent thereafter to be considered as the result of mere historical mistakes."

Thus, the great villain is "Nebuchadnezzar, who ruled over the ''Assyrian

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, the indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

* Assyrian ...

s''" (1:1), yet the historical Nebuchadnezzar II was the king of Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

. Other details, such as fictional place names, the immense size of armies and fortifications, and the dating of events, cannot be reconciled with the historical record. Judith's village, Bethulia (literally "virginity") is unknown and otherwise unattested to in any ancient writing.

Nevertheless, there have been various attempts by both scholars and clergy to understand the characters and events in the Book as allegorical representations of actual personages and historical events. Much of this work has focused on linking Nebuchadnezzar with various conquerors of Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Hebrew language#Modern Hebrew, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian vocalization, Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous L ...

from different time periods and, more recently, linking Judith herself with historical female leaders, including Queen Salome Alexandra, Judea's only female monarch (76–67 BC) and its last ruler to die while Judea remained an independent kingdom.

Identification of Nebuchadnezzar with Artaxerxes III Ochus

The identity of Nebuchadnezzar was unknown to theChurch Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

, but some of them attempted an improbable identification with Artaxerxes III Ochus

Ochus ( grc-gre, Ὦχος ), known by his dynastic name Artaxerxes III ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 359/58 to 338 BC. He was the son and successor of ...

(425–338 BC), not on the basis of the character of the two rulers, but due to the presence of a "Holofernes" and a "Bagoas" in Ochus' army.Noah Calvin Hirschy, ''Artaxerxes III Ochus and His Reign'', p. 81 (Univ. of Chicago Press 1909). This view also gained currency with scholarship in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Identification of Nebuchadnezzar with Ashurbanipal

In his comparison between the Book of Judith and Assyrian history, Catholic priest and scholar Fulcran Vigouroux (1837–1915) attempts an identification of Nabuchodonosor king of Assyria with Ashurbanipal (668–627 BC) and his rivalArphaxad

Arpachshad ( he, אַרְפַּכְשַׁד – ''ʾArpaḵšaḏ'', in pausa – ''ʾArpaḵšāḏ''; gr, Ἀρφαξάδ – ''Arphaxád''), alternatively spelled Arphaxad or Arphacsad, is one of the postdiluvian men in the ShemTera ...

king of the Medes

The Medes (Old Persian: ; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, the ...

with Phraortes

Phraortes ( peo, 𐎳𐎼𐎺𐎼𐎫𐎡𐏁, translit=Fravartiš; grc, Φραόρτης, translit=Phraórtēs; died c. 653 BC), son of Deioces, was the second king of the Median Empire.

Like his father Deioces, Phraortes started wars agains ...

(665–653 BC), the son of Deioces

Deioces ( grc, Δηιόκης), from the Old Iranian ''Dahyu-ka-'', meaning "the lands" (above, on and beneath the earth), was the founder and the first ''shah'' as well as priest of the Median Empire. His name has been mentioned in different for ...

, founder of Ecbatana

Ecbatana ( peo, 𐏃𐎥𐎶𐎫𐎠𐎴 ''Hagmatāna'' or ''Haŋmatāna'', literally "the place of gathering" according to Darius I's inscription at Bisotun; Persian: هگمتانه; Middle Persian: 𐭠𐭧𐭬𐭲𐭠𐭭; Parthian: 𐭀𐭇� ...

.

As argued by Vigouroux, the two battles mentioned in the Septuagint version of the Book of Judith are a reference to the clash of the two empires in 658–657 and to Phraortes' death in battle in 653, after which Ashurbanipal continued his military actions with a large campaign starting with the Battle of the Ulaya River (652 BC) on the 18th year of this Assyrian king. Contemporary sources make reference to the many allies of Chaldea (governed by Ashurbanipal's rebel brother Shamash-shum-ukin

Shamash-shum-ukin ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning "Shamash has established the name"), was king of Babylon as a vassal of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 668 BC to his death in 648. Born into the Assyrian royal family, Shamash-shum-ukin was ...

), including the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah

The Kingdom of Judah ( he, , ''Yəhūdā''; akk, 𒅀𒌑𒁕𒀀𒀀 ''Ya'údâ'' 'ia-ú-da-a-a'' arc, 𐤁𐤉𐤕𐤃𐤅𐤃 ''Bēyt Dāwīḏ'', " House of David") was an Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. Ce ...

, which were subjects of Assyria and are mentioned in the Book of Judith as victims of Ashurbanipal's Western campaign.

During that period, as in the Book of Judith, there was no king in Judah since the legitimate sovereign, Manasseh of Judah

Manasseh (; Hebrew: ''Mənaššé'', "Forgetter"; akk, 𒈨𒈾𒋛𒄿 ''Menasî'' 'me-na-si-i'' grc-gre, Μανασσῆς ''Manasses''; la, Manasses) was the fourteenth king of the Kingdom of Judah. He was the oldest of the sons of Hezekia ...

, was being held captive in Nineveh at this time. As a typical policy of the time, all leadership was thus transferred in the hands of the High Priest of Israel in charge, which was Joakim in this case (''Judith ''4:6). The profanation of the temple (''Judith'' 4:3) might have been that under king Hezekiah

Hezekiah (; hbo, , Ḥīzqīyyahū), or Ezekias); grc, Ἐζεκίας 'Ezekías; la, Ezechias; also transliterated as or ; meaning "Yahweh, Yah shall strengthen" (born , sole ruler ), was the son of Ahaz and the 13th king of Kingdom of Jud ...

(see 2 Chronicles, xxix, 18–19), who reigned between c. 715 and 686 BC.

Although Nebuchadnezzar and Ashurbanipal's campaigns show direct parallels, the main incident of Judith's intervention has never been recorded in official history. Additionally, the reasons for the name changes are difficult to understand, unless the text was transmitted without character names before they were added by the Greek translator, who lived centuries later. Moreover, Ashurbanipal is never referenced by name in the Bible, except perhaps for the corrupt form " Asenappar" in 2 Chronicles and Ezra

Ezra (; he, עֶזְרָא, '; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (, ') and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, was a Jewish scribe (''sofer'') and priest (''kohen''). In Greco-Latin Ezra is called Esdras ( grc-gre, Ἔσδρας ...

4:10 or the anonymous title "The King of Assyria" in the 2 Kings, which means his name might have never been recorded by Jewish historians.

Identification of Nebuchadnezzar with Tigranes the Great

Modern scholars argue in favor of a 2nd–1st century context for the Book of Judith, understanding it as a sort ofroman à clef

''Roman à clef'' (, anglicised as ), French for ''novel with a key'', is a novel about real-life events that is overlaid with a façade of fiction. The fictitious names in the novel represent real people, and the "key" is the relationship ...

, i.e. a literary fiction whose characters stand for some real historical figure, generally contemporary to the author. In the case of the Book of Judith, Biblical scholar Gabriele Boccaccini, identified Nebuchadnezzar with Tigranes the Great

Tigranes II, more commonly known as Tigranes the Great ( hy, Տիգրան Մեծ, ''Tigran Mets''; grc, Τιγράνης ὁ Μέγας ''Tigránes ho Mégas''; la, Tigranes Magnus) (140 – 55 BC) was King of Armenia under whom the ...

(140–56 BC), a powerful King of Armenia

This is a list of the monarchs of Armenia, for more information on ancient Armenia and Armenians, please see History of Armenia. For information on the medieval Armenian Kingdom in Cilicia, please see the separate page Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia.

...

who, according to Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for ''The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

and Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

, conquered all of the lands identified by the Biblical author in Judith.

Under this theory, the story, although fictional, would be set in the time of Queen Salome Alexandra

Salome Alexandra, or Shlomtzion ( grc-gre, Σαλώμη Ἀλεξάνδρα; he, , ''Šəlōmṣīyyōn''; 141–67 BCE), was one of three women to rule over Judea, the other two being Athaliah and Devora. The wife of Aristobulus I, and ...

, the only Jewish regnant queen, who reigned over Judea from 76 to 67 BC.

Like Judith, the Queen had to face the menace of a foreign king who had a tendency to destroy the temples of other religions. Both women were widows whose strategical and diplomatic skills helped in the defeat of the invader. Both stories seem to be set at a time when the temple had recently been rededicated, which is the case after Judas Maccabee killed Nicanor and defeated the Seleucids

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

. The territory of Judean occupation includes the territory of Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first- ...

, something which was possible in Maccabean times only after John Hyrcanus

John Hyrcanus (; ''Yōḥānān Hurqanōs''; grc, Ἰωάννης Ὑρκανός, Iōánnēs Hurkanós) was a Hasmonean ( Maccabean) leader and Jewish high priest of the 2nd century BCE (born 164 BCE, reigned from 134 BCE until his death in ...

reconquered those territories. Thus, the presumed Sadducee

The Sadducees (; he, צְדוּקִים, Ṣədūqīm) were a socio- religious sect of Jewish people who were active in Judea during the Second Temple period, from the second century BCE through the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. Th ...

author of Judith would desire to honor the great (Pharisee) Queen who tried to keep both Sadducees and Pharisees united against the common menace.

Place names specific to the Book of Judith

Whilst a number of the places referred to are familiarbiblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

or modern place names, there are others which are considered fictional or whose location is not otherwise known. These include:

*1:5 - the territory of Ragae, possible Rages or Rhages, cf. Tobit 1:16

*1:6 - the rivers Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

and Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

are mentioned, as well as the Hydaspes (Jadason in the Vulgate

The Vulgate (; also called (Bible in common tongue), ) is a late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bible.

The Vulgate is largely the work of Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Gospels u ...

). Hydaspes is also the Greek name for the Jhelum River

The Jhelum River (/dʒʰeːləm/) is a river in the northern Indian subcontinent. It originates at Verinag and flows through the Indian administered territory of Jammu and Kashmir, to the Pakistani-administered territory of Kashmir, and then ...

in modern India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

*2:21 - the plain of Bectileth, three days' march from Nineveh

*4:4 - Kona

*4:4 - Belmain

*4:4 - Choba

*4:4 - Aesora. The Septuagint calls it ''Aisora'', ''Arasousia'', ''Aisoraa'', or ''Assaron'', depending on the manuscript.

*4:4 - The valley of Salem

*4:6 and several later references - Bethulia, a gated city (Judith 10:6). From the gates of the city, the valley below can be observed (Judith 10:10)

*4:6 - Betomesthaim or Betomasthem. Some translations refer to "the people of Bethulia and Betomesthaim" as a unit, which "faces (''singular'') Esdraelon

The Jezreel Valley (from the he, עמק יזרעאל, translit. ''ʿĒmeq Yīzrəʿēʿl''), or Marj Ibn Amir ( ar, مرج ابن عامر), also known as the Valley of Megiddo, is a large fertile plain and inland valley in the Northern Distr ...

opposite the plain near Dothan. The Encyclopaedia Britannica

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles ...

refers to the "Plain of Esdraelon" as the plain between the Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Galil ...

hills and Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first- ...

.

*4:6 - A plain near Dothan Dothan is a place-name from the Hebrew Bible, identified with Tel Dothan. It may refer to:

* Dothan, Alabama, a city in Dale, Henry, and Houston counties in the U.S. state of Alabama

* Dani Dothan, lyricist and vocalist for the Israeli rock and ne ...

(Dothian in the Vulgate)

*7:3 - Cyalon or Cynamon, also facing Esdraelon. The ''Encyclopedia of the Bible'' notes that "some scholars have felt that this name is a corruption for Jokneam", but its editors argue that there is "little evidence to support this conjecture".

*7:18 - Egrebeh, which is near Chubi, beside the Wadi Mochmur.

*8:4 - Balamon. Some versions state that Manasseh, Judith's husband, had been buried in a field between Dothan and Balamon (Jerusalem Bible

''The Jerusalem Bible'' (JB or TJB) is an English translation of the Bible published in 1966 by Darton, Longman & Todd. As a Catholic Bible, it includes 73 books: the 39 books shared with the Hebrew Bible, along with the seven deuterocanonica ...

, New Revised Standard Version); others state that he was buried in Bethulia where he had died (Vulgate, Douay-Rheims 1899 American Edition).

*15:4 - Along with Betomesthaim, some authorities also mention Bebai.

Later artistic renditions

The character of Judith is larger than life, and she has won a place in Jewish and Christian lore, art, poetry and drama. Her name, which means "she will be praised" or "woman of Judea", suggests that she represents the heroic spirit of the Jewish people, and that same spirit, as well as her chastity, have endeared her to Christianity. Owing to her unwavering religious devotion, she is able to step outside of her widow's role, and dress and act in a sexually provocative manner while clearly remaining true to her ideals in the reader's mind, and her seduction and beheading of the wicked Holofernes while playing this role has been rich fodder for artists of various genres.In literature

The first extant commentary on The Book of Judith is by

The first extant commentary on The Book of Judith is by Hrabanus Maurus

Rabanus Maurus Magnentius ( 780 – 4 February 856), also known as Hrabanus or Rhabanus, was a Frankish Benedictine monk, theologian, poet, encyclopedist and military writer who became archbishop of Mainz in East Francia. He was the author of t ...

(9th century). Thenceforth her presence in medieval European literature is robust: in homilies, biblical paraphrases, histories and poetry. An Old English poetic version is found together with Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ang, Bēowulf ) is an Old English epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature. The ...

(their epics appear both in the Nowell Codex

The Nowell Codex is the second of two manuscripts comprising the bound volume Cotton MS Vitellius A XV, one of the four major Anglo-Saxon poetic manuscripts. It is most famous as the manuscript containing the unique copy of the epic poem '' Beo ...

). "The opening of the poem is lost (scholars estimate that 100 lines were lost) but the remainder of the poem, as can be seen, the poet reshaped the biblical source and set the poem's narrative to an Anglo-Saxon audience."

At the same time she is the subject of a homily by the Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

abbot Ælfric Ælfric (Old English ', Middle English ''Elfric'') is an Anglo-Saxon given name.

Churchmen

*Ælfric of Eynsham (c. 955–c. 1010), late 10th century Anglo-Saxon abbot and writer

*Ælfric of Abingdon (died 1005), late 10th century Anglo-Saxon Archbi ...

. The two conceptual poles represented by these works will inform much of Judith's subsequent history.

In the epic, she is the brave warrior, forceful and active; in the homily she is an exemplar of pious chastity for cloistered nuns. In both cases, her narrative gained relevance from the Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

invasions of the period. Within the next three centuries Judith would be treated by such major figures as Heinrich Frauenlob

Heinrich Frauenlob (between 1250 and 1260 – 29 November 1318), sometimes known as Henry of Meissen (''Heinrich von Meißen''), was a Middle High German literature, Middle High German poet, a representative of both the ''Spruchdichtung, Sangspruch ...

, Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: '' ...

, and Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He wa ...

.

In medieval Christian art, the predominance of church patronage assured that Judith's patristic valences as "Mulier Sancta" and Virgin Mary prototype would prevail: from the 8th-century frescoes in Santa Maria Antigua in Rome through innumerable later bible miniatures. Gothic cathedrals often featured Judith, most impressively in the series of 40 stained glass panels at the Sainte-Chapelle

The Sainte-Chapelle (; en, Holy Chapel) is a royal chapel in the Gothic style, within the medieval Palais de la Cité, the residence of the Kings of France until the 14th century, on the Île de la Cité in the River Seine in Paris, France.

...

in Paris (1240s).

In Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

literature and visual arts, all of these trends were continued, often in updated forms, and developed. The already well established notion of Judith as an ''exemplum

An exemplum (Latin for "example", pl. exempla, ''exempli gratia'' = "for example", abbr.: ''e.g.'') is a moral anecdote, brief or extended, real or fictitious, used to illustrate a point. The word is also used to express an action performed by an ...

'' of the courage of local people against tyrannical rule from afar was given new urgency by the Assyrian nationality of Holofernes, which made him an inevitable symbol of the threatening Turks. The Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

poet Lucrezia Tornabuoni

Lucrezia Tornabuoni (22 June 1427 – 25 March 1482) was an influential Italian political adviser and author during the 15th century. She was a member of one of the most powerful Italian families of the time and married Piero di Cosimo de' Medi ...

chose Judith as one of the five subjects of her poetry on biblical figures.

A similar dynamic was created in the 16th century by the confessional strife of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Both Protestants and Catholics draped themselves in the protective mantle of Judith and cast their "heretical" enemies as Holofernes.

In 16th-century France, writers such as Guillaume Du Bartas, Gabrielle de Coignard

Gabrielle de Coignard (1550?–1586) was a Toulousaine devotional poet in 16th-century France. She is most well known for her posthumously published book of religious poetry, ''Oeuvres chrétiennes'' ("Christian Works"), and her marriage into the ...

and Anne de Marquets Anne de Marquets was a French Catholic nun and poet from the . She was likely born around 1533 in the Comté d'Eu of a noble family.Feugère, 1860, p. 63.

Biography

She entered the convent at Poissy at a very young age, where she proved to be gifte ...

composed poems on Judith's triumph over Holofernes. Croatian poet and humanist Marko Marulić

Marko Marulić Splićanin (), in Latin Marcus Marulus Spalatensis (18 August 1450 – 5 January 1524), was a Croatian poet, lawyer, judge, and Renaissance humanist who coined the term "psychology". He is the national poet of Croatia. According to ...

also wrote an epic on Judith's story in 1501, the ''Judita

''Judita'' (Judith) is one of the most important Croatian literary works, an epic poem written by the "father of Croatian literature" Marko Marulić in 1501.

Editions

The work was finished on April 22, 1501, and was published three times durin ...

''. Italian poet and scholar Bartolomeo Tortoletti wrote a Latin epic on the Biblical character of Judith (''Bartholomaei Tortoletti Iuditha uindex e uindicata'', 1628). The Catholic tract ''A Treatise of Schisme'', written in 1578 at Douai by the English Roman Catholic scholar Gregory Martin, included a paragraph in which Martin expressed confidence that "the Catholic Hope would triumph, and pious Judith would slay Holofernes". This was interpreted by the English Protestant authorities at the time as incitement to slay Queen Elizabeth I. It served as the grounds for the death sentence passed on printer William Carter who had printed Martin's tract and who was executed in 1584.

In painting and sculpture

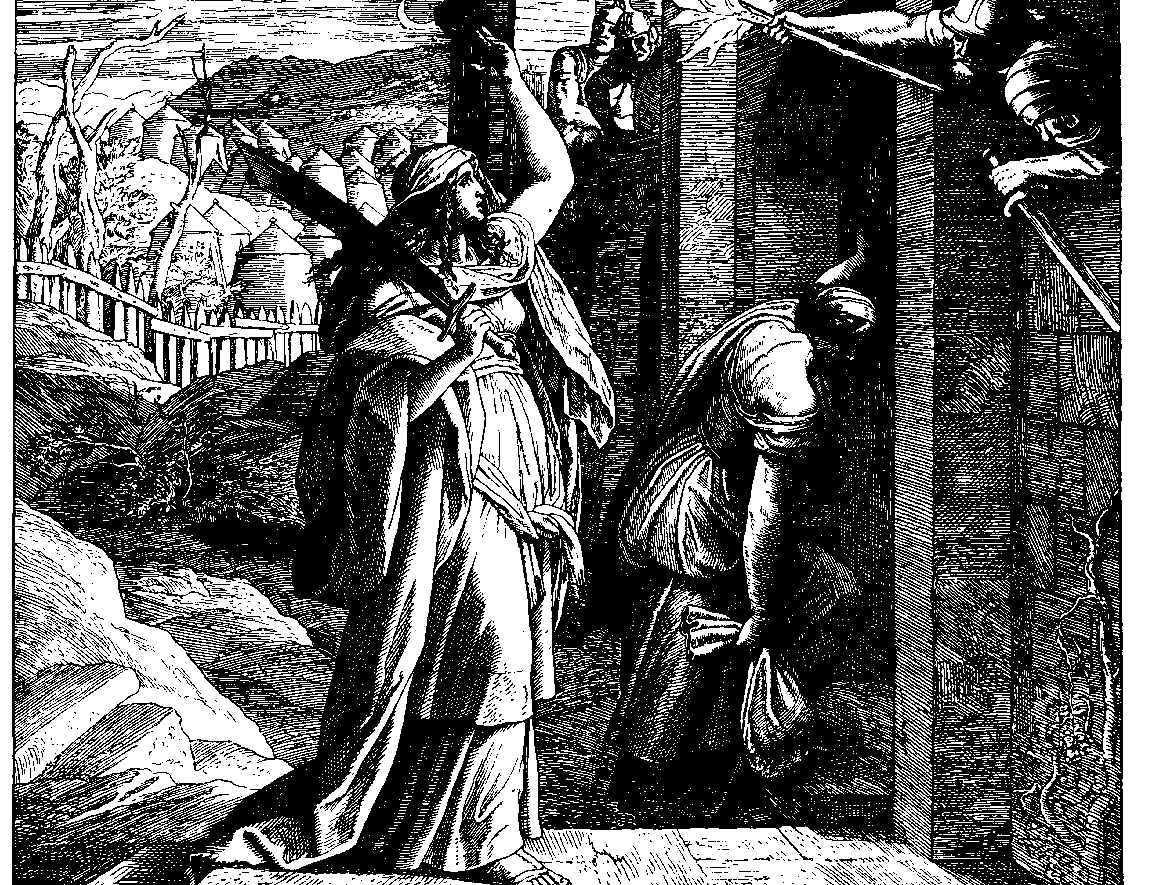

The subject is one of the most commonly shown in the

The subject is one of the most commonly shown in the Power of Women

The "Power of Women" (german: Weibermacht) is a medieval and Renaissance artistic and literary topos, showing "heroic or wise men dominated by women", presenting "an admonitory and often humorous inversion of the male-dominated sexual hierarc ...

''topos''. The account of Judith's beheading of Holofernes has been treated by several painters and sculptors, most notably Donatello

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi ( – 13 December 1466), better known as Donatello ( ), was a Republic of Florence, Florentine sculptor of the Renaissance period. Born in Republic of Florence, Florence, he studied classical sculpture and use ...

and Caravaggio

Michelangelo Merisi (Michele Angelo Merigi or Amerighi) da Caravaggio, known as simply Caravaggio (, , ; 29 September 1571 – 18 July 1610), was an Italian painter active in Rome for most of his artistic life. During the final four years of hi ...

, as well as Sandro Botticelli

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi ( – May 17, 1510), known as Sandro Botticelli (, ), was an Italian Renaissance painting, Italian painter of the Early Renaissance. Botticelli's posthumous reputation suffered until the late 19th cent ...

, Andrea Mantegna

Andrea Mantegna (, , ; September 13, 1506) was an Italian painter, a student of Roman archeology, and son-in-law of Jacopo Bellini.

Like other artists of the time, Mantegna experimented with perspective, e.g. by lowering the horizon in order ...

, Giorgione

Giorgione (, , ; born Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco; 1477–78 or 1473–74 – 17 September 1510) was an Italian painter of the Venetian school during the High Renaissance, who died in his thirties. He is known for the elusive poetic qualit ...

, Lucas Cranach the Elder

Lucas Cranach the Elder (german: Lucas Cranach der Ältere ; – 16 October 1553) was a German Renaissance painter and printmaker in woodcut and engraving. He was court painter to the Electors of Saxony for most of his career, and is know ...

, Titian

Tiziano Vecelli or Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italians, Italian (Republic of Venice, Venetian) painter of the Renaissance, considered the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school (art), ...

, Horace Vernet

Émile Jean-Horace Vernet (30 June 178917 January 1863), more commonly known as simply Horace Vernet, was a French Painting, painter of battles, portraits, and Orientalism, Orientalist subjects.

Biography

Vernet was born to Carle Vernet, another ...

, Gustav Klimt

Gustav Klimt (July 14, 1862 – February 6, 1918) was an Austrian symbolist painter and one of the most prominent members of the Vienna Secession movement. Klimt is noted for his paintings, murals, sketches, and other objets d'art. Klimt's prim ...

, Artemisia Gentileschi, Jan Sanders van Hemessen

Jan Sanders van Hemessen (c. 1500 – c. 1566) was a leading Flemish Renaissance painter, belonging to the group of Italianizing Flemish painters called the Romanists, who were influenced by Italian Renaissance painting. Van Hemessen had v ...

, Trophime Bigot

Trophime Bigot (1579–1650), also known as Théophile Bigot, Teofili Trufemondi, the Candlelight Master (''Maître à la Chandelle''), was a French painter of the Baroque era, active in Rome and his native Provence.

Bigot was born in Arles in 1 ...

, Francisco Goya

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (; ; 30 March 174616 April 1828) was a Spanish romantic painter and printmaker. He is considered the most important Spanish artist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. His paintings, drawings, and e ...

, Francesco Cairo

Francesco Cairo (26 September 1607 – 27 July 1665), also known as Francesco del Cairo, was an Italian Baroque painter active in Lombardy and Piedmont.

Biography

He was born and died in Milan. It is not known where he obtained his early trai ...

and Hermann-Paul

René Georges Hermann-Paul (27 December 1864 – 23 June 1940) was a French artist. He was born in Paris and died in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer.

He was a well-known illustrator whose work appeared in numerous newspapers and periodicals. His fine art ...

. Also, Michelangelo depicts the scene in multiple aspects in one of the Pendentives, or four spandrels on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel

The Sistine Chapel (; la, Sacellum Sixtinum; it, Cappella Sistina ) is a chapel in the Apostolic Palace, the official residence of the pope in Vatican City. Originally known as the ''Cappella Magna'' ('Great Chapel'), the chapel takes its name ...

. Judy Chicago

Judy Chicago (born Judith Sylvia Cohen; July 20, 1939) is an American feminist artist, art educator, and writer known for her large collaborative art installation pieces about birth and creation images, which examine the role of women in history ...

included Judith with a place setting in ''The Dinner Party

''The Dinner Party'' is an installation artwork by feminist artist Judy Chicago. Widely regarded as the first epic feminist artwork, it functions as a symbolic history of women in civilization. There are 39 elaborate place settings on a triangul ...

''.

In music and theatre

The famous 40-voice motet ''Spem in alium

''Spem in alium'' (Latin for "Hope in any other") is a 40-part Renaissance motet by Thomas Tallis, composed in c. 1570 for eight choirs of five voices each. It is considered by some critics to be the greatest piece of English early music. H. B. ...

'' by English composer Thomas Tallis

Thomas Tallis (23 November 1585; also Tallys or Talles) was an English composer of High Renaissance music. His compositions are primarily vocal, and he occupies a primary place in anthologies of English choral music. Tallis is considered one ...

, is a setting of a text from the Book of Judith. The story also inspired oratorios

An oratorio () is a large musical composition for orchestra, choir, and soloists. Like most operas, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias. However, opera is mu ...

by Antonio Vivaldi, W. A. Mozart and Hubert Parry

Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry, 1st Baronet (27 February 18487 October 1918) was an English composer, teacher and historian of music. Born in Richmond Hill in Bournemouth, Parry's first major works appeared in 1880. As a composer he is b ...

, and an operetta by Jacob Pavlovitch Adler

Jacob Pavlovich Adler (Yiddish: יעקבֿ פּאַװלאָװיטש אַדלער; born Yankev P. Adler; February 12, 1855 – April 1, 1926)IMDB biography was a Jewish actor and star of Yiddish theater, first in Odessa, and later in London and ...

. Marc-Antoine Charpentier

Marc-Antoine Charpentier (; 1643 – 24 February 1704) was a French Baroque composer during the reign of Louis XIV. One of his most famous works is the main theme from the prelude of his ''Te Deum'', ''Marche en rondeau''. This theme is still us ...

has composed, ''Judith sive Bethulia liberata'' H.391, oratorio for soloists, chorus, 2 flutes, strings, and continuo (? mid-1670s). Elisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sc ...

(EJG.30) and Sébastien de Brossard have composed a cantate Judith.

Alessandro Scarlatti

Pietro Alessandro Gaspare Scarlatti (2 May 1660 – 22 October 1725) was an Italian Baroque composer, known especially for his operas and chamber cantatas. He is considered the most important representative of the Neapolitan school of opera.

...

wrote an oratorio in 1693, ''La Giuditta :''To be distinguished from Giuditta a German operetta by Franz Lehár.''

Note La Giuditta may refer to one of several Italian oratorios, further elaborated below.

Each version of La Giuditta deals with the figure of Judith, from the Biblical A ...

'', as did the Portuguese composer Francisco António de Almeida in 1726; ''Juditha triumphans

''Juditha triumphans devicta Holofernis barbarie'' (Latin: 'Judith triumphant over the barbarians of Holofernes'), RV 644, is an oratorio by Antonio Vivaldi, the only survivor of the four that he is known to have composed. Although the rest of ...

'' was written in 1716 by Antonio Vivaldi; Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his ra ...

composed in 1771 ''La Betulia Liberata

''La '' (''The Liberation of Bethulia'') is a libretto by Pietro Metastasio which was originally commissioned by Emperor Charles VI and set to music by Georg Reutter the Younger in 1734. It was subsequently set by as many as 30 composers, includ ...

'' (KV 118), to a libretto by Pietro Metastasio

Pietro Antonio Domenico Trapassi (3 January 1698 – 12 April 1782), better known by his pseudonym of Pietro Metastasio (), was an Italian poet and librettist, considered the most important writer of ''opera seria'' libretti.

Early life

Met ...

. Arthur Honegger

Arthur Honegger (; 10 March 1892 – 27 November 1955) was a Swiss composer who was born in France and lived a large part of his life in Paris. A member of Les Six, his best known work is probably ''Antigone'', composed between 1924 and 1927 to ...

composed an oratorio, ''Judith'', in 1925 to a libretto by René Morax

René Morax (11 May 1873 – 3 January 1963) was a Swiss writer, playwright, stage director and theatre manager. He founded the Théâtre du Jorat in Morges in 1908, and promoted historical and rural theatre in French in Switzerland. He is known fo ...

. Operatic treatments exist by Russian composer Alexander Serov

Alexander Nikolayevich Serov (russian: Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Серо́в, Saint Petersburg, – Saint Petersburg, ) was a Russian composer and music critic. He is notable as one of the most important music critics in ...

, '' Judith'', by Austrian composer Emil von Reznicek

Emil Nikolaus Joseph, Freiherr von Reznicek (4 May 1860, in Vienna – 2 August 1945, in Berlin) was an Austrian composer of Romanian-Czech ancestry.

Life

Reznicek's grandfather, Josef Resnitschek (1787–1848), was a trumpet virtuoso and b ...

, ''Holofernes'', and '' Judith'' by German composer Siegfried Matthus. The French composer Jean Guillou wrote his Judith-Symphonie for Mezzo and Orchestra in 1970, premiered in Paris in 1972 and published by Schott-Music.

In 1840, Friedrich Hebbel

Christian Friedrich Hebbel (18 March 1813 – 13 December 1863) was a German poet and dramatist.

Biography

Hebbel was born at Wesselburen in Dithmarschen, Holstein, the son of a bricklayer. He was educated at the ''Gelehrtenschule des Johanneu ...

's play '' Judith'' was performed in Berlin. He deliberately departs from the biblical text:

I have no use for the biblical Judith. There, Judith is a widow who lures Holofernes into her web with wiles, when she has his head in her bag she sings and jubilates with all of Israel for three months. That is mean, such a nature is not worthy of her success .. My Judith is paralyzed by her deed, frozen by the thought that she might give birth to Holofernes' son; she knows that she has passed her boundaries, that she has, at the very least, done the right thing for the wrong reasons.The story of Judith has been a favourite of latter-day playwrights; it was brought alive in 1892 by

Abraham Goldfaden

Abraham Goldfaden (Yiddish: אַבֿרהם גאָלדפֿאַדען; born Avrum Goldnfoden; 24 July 1840 – 9 January 1908), also known as Avram Goldfaden, was a Russian-born Jewish poet, playwright, stage director and actor in the languages Yid ...

, who worked in Eastern Europe. The American playwright Thomas Bailey Aldrich

Thomas Bailey Aldrich (; November 11, 1836 – March 19, 1907) was an American writer, poet, critic, and editor. He is notable for his long editorship of ''The Atlantic Monthly'', during which he published writers including Charles W. Chesnutt. ...

's ''Judith of Bethulia'' was first performed in New York, 1905, and was the basis for the 1914 production ''Judith of Bethulia

''Judith of Bethulia'' (1914 in film, 1914) is an American film starring Blanche Sweet and Henry B. Walthall, and produced and directed by D. W. Griffith, based on the play "Judith and the Holofernes" (1896) by Thomas Bailey Aldrich, which itself ...

'' by director D. W. Griffith. A full hour in length, it was one of the earliest feature films made in the United States. English writer Arnold Bennett

Enoch Arnold Bennett (27 May 1867 – 27 March 1931) was an English author, best known as a novelist. He wrote prolifically: between the 1890s and the 1930s he completed 34 novels, seven volumes of short stories, 13 plays (some in collaboratio ...

in 1919 tried his hand at dramaturgy with ''Judith'', a faithful reproduction in three acts; it premiered in spring 1919 at Devonshire Park Theatre, Eastbourne.Gutenberg Ed.

Moshe Shamir

Moshe Shamir ( he, משה שמיר; 15 September 1921 – 20 August 2004) was an Israeli author, playwright, opinion writer, and public figure. He was the author of a play upon which Israeli film '' He Walked Through the Fields'' was based.

Biogr ...

was performed in Israel. Shamir examines the question why the story of Judith was excluded from the Jewish (Hebrew) Bible and thus banned from Jewish history. In putting her story on stage he tries to reintegrate Judith's story into Jewish history. English playwright Howard Barker

Howard Barker (born 28 June 1946) is a British playwright, screenwriter and writer of radio drama, painter, poet, and essayist writing predominantly on playwriting and the theatre. The author of an extensive body of dramatic works since the 197 ...

examined the Judith story and its aftermath, first in the scene "The Unforeseen Consequences of a Patriotic Act", as part of his collection of vignettes, ''The Possibilities''. Barker later expanded the scene into a short play ''Judith''.

Notes

References

Further reading

* * *External links

The Book of Judith

Full text (also available i

* Craven, Ton

Judith: Apocrypha

''The Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women'' 31 December 1999 at Jewish Women's Archive * Toy, Crawford Howell; Charles Cutler Torrey, Torrey, Charles C.

JUDITH, BOOK OF

at ''The Jewish Encyclopedia'', 1906 * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Judith, Book of Book of Judith Deuterocanonical books Ancient Hebrew texts Historical novels Jewish apocrypha Biblical women in ancient warfare Historical books